Learning how to cycle at 40

As a child, I never learned how to ride a bike. I grew up when bicycles were still largely just a means of transport, not merely the fun or fitness things they have since become for many Nairobians. For a rural girl growing up in Wangige in the 80s, riding a bicycle was considered an act of truancy reserved only for those who earned the infamous title of Wanja kĩhĩĩ.

The Wangige you see today- a farming town in Lower Kabete, Kiambu County with an eponymous market and the egg capital of East Africa- is not the Wangige of the 1980s to early 2000s. Don’t let the new veneer of bougieness fool you.

Before Wangige market transformed into a metropolitan town complete with an interchange along the Western bypass, she was a timid village girl who walked to school ( Ndunyu Primary) barefooted carrying; ashes with polythene bags, the branches of a wattle tree (brooms) in one hand, and a jerrican of water in the other. Twice a week she cleaned classrooms with the jerrican water and with the ashes and wattle tree branches, latrines.

Wangige imeoga na kurudi soko tu juzi.

In the last 10 years alone the town has washed off its bright red muddy shoes only to walk into dens of illicit brews, drug abuse and trafficking. But this is not a story about my shags. This is the story of a village girl who never learnt how to ride a bike until she was Mama Nanii.

Black Mambas and the gendering of bicycle riding

‘

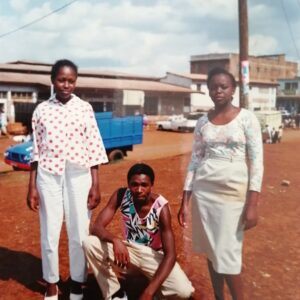

Yours truly with my cousins Njeri & Ndung’u at the famous Wangige Market Circa 1998

Maithikiri’ is a word that only became part of my vocabulary in the late 90s, well after high school as I watched my much younger cousins borrow rides from the neighbourhood kids. Bikes and bought toys were for rich kids.

We made our own fun and toys with what was there in the village, farmlands, forests and rivers; placing two firm sticks on used tyres and racing with them, pouring water up a hill and doing nyororoka (slidos), tying old rags into a ball and playing ju (kati).

The only bikes I ever saw then were Black Mambas. Those were not bikes for children to ride for fun. Black mambas were for grown men to carry sacks and crates of market and farm, stacks of firewood, or passengers.

Wangige is where my childhood innocence of being ok not knowing how to ride a bicycle gave way to a motherhood of regret at having been robbed of a childhood right of passage.

Mum, how come you can’t ride a bike?

Riding with Stano towards Wangige along the Western Bypass

Yet, before Mo, our third-born son began cycling, it never really used to bother me. Neither did I feel like I had failed to learn an important life skill. It was Mo who pried open the floodgates of pent-up childhood cravings. And boy did I wallow! Seeing him at only 6 years doing wheelies, scramboos and all manner of out-of-this-world stunts lit a bonfire under my competitive ass.

At 39, I vowed to myself, for my 40th Birthday, I would not only learn how to ride, but I would also buy a bicycle. In May 2022, I did both.

Fear had other plans in a kiondo waiting for me.

A few months into my riding lessons and with wobbly legs and arms, I let fear consume me. I simply couldn’t get on the road. I kept seeing myself being hit and suffering a bad fall or injury and that fear put my rides on a leash that went as far as a few meters of our neighbourhood cabro. In the end, fear won.

Then last year in November, I signed up for cycling lessons with Stano of CatSkills, a company based in Zambezi, Limuru that offers personal raining & my running gear plug. Stano is an avid cyclist who enjoys the outdoors more on his two wheels than he does on his heels. Running, he tells me, is more gruelling.

A week later, I was at the road construction site for the new Gitaru interchange learning the basics.

Stano is like the platonic ideal of a fitness coach: supportive, meticulous at planning the takeaway from each lesson, and equipped with an arsenal of stories of his escapades and near-death misses for motivation.

You should have seen me. I was like an elephant on a tricycle. No matter how hard I tried, I could not get my left leg to listen. It was frustrating. Stano was doing everything to keep me steady but with cycling, no one can mount for you. And practising hopping on and off takes the patience of a monk.

Five days later, I was mounting on a flat and slightly hilly course and pedalling on my own. Ngemis could be heard all the way in Ndenderu as the big concrete boulders all in unison exclaimed;

“tunaride boda boda, tunaride boda boda”

Of men and the eyes of frogs

Stano ni Cycologist.

While I was prepared for the reactions my learning to cycle in such open spaces would elicit, what I was not prepared for was how entitled some men feel to women’s experiences, actions and bodies. The intensity and consistency of it left me reeling for days after every lesson.

In the 3 weeks that I went to our training ground, I received all manner of unsolicited opinions from men; some on foot, some on boda bodas, some on matatus, some on private cars, some at the construction and others at vibandas.

“Mama kalia kiti vizuri”

“Madam mbona haujua baiskeli na vile wewe mkubwa”

“Nikuje nikusaidie”

“Wacha kuogopa”

Every single lesson was another day of drunk men, stoned men, and idle men giving me advice on where I was going wrong and how fast I ought to be going.

All came to a head during one of our rides after I had mastered the courage to ride on a highway. A stoned or drunk guy (he looked like he was both) on boda nearly grabbed my shaky hands as I unsteadily struggled to coordinate pedalling up a hill, keeping to my lane, looking ahead and planning my next move should the oncoming pedestrians decide not to move out of the way. It took everything in me not to stop right there and slap the living daylights out of him.

Stano, incensed shouted, “Wewe! Ni za nini hizo?”.

The drunk just smirked.

It was only after we came to the top of that hill that I placed my bicycle next to the metallic rail, leaned back and spewed all the fire and brimstone that had been burning all my insides turning my tongue black right there by the side of the road.

“Pole,” Stano said.

From the look in his eyes, I could tell that that incident had also left him livid at having to keep carrying the weight of shame of men and their sense of entitlement over and over, knowing that saying “not all men” sometimes is never enough.

For a 40-year-old, there is more to cycling

Posing with the bike looking like a serious rider. I hadn’t even learnt how to mount yet

It was the most brazen entitlement to my cycling body by a man that I had experienced. A portend of how my life as a female cyclist in Kenya. As I sat there on that rail calming my breath and nerves, a proverb I girded my mind with the first day of cycling swallowed me like a boat on a stormy sea.

‘Maitho ma ciũra matigiragia ng’ombe inyue maĩ’ The eyes of frogs do not stop cows from quenching their thirst.

I knew from day one that I would need to know how to deal with all manner of reactions, all the eyes their words showed, not spoken. Learning to cycle at 40 is to be that unfazed by the eyes (and mouths) of frogs, staring, jeering, catcalling you trying to frazzle you. For a 40-year-old woman, there is more to learning than just balancing, pedalling and developing situational awareness.

It is more about learning to drown out the noise and ignore the eyes of frogs. It is quickly realizing that this is not just a cycling lesson by a life lesson. It’s about never letting the eyes or lips of others stop you from quenching your thirst for more in life.

As my fear of riding alongside matatus, boda bodas and pedestrians slowly dissipates, I keep telling myself, yaani there will come a time when cycling 50 even 100 km will feel like I was born on a bicycle.

For our last lesson, Stano and I together rode the 10 km of the Western Bypass to Wangige and back. Going back to this place where over two decades ago, this was merely a piped dream, I felt a rush of justice from a dream deferred wash all over me. For hundreds of women though, those dreams is still on hold.